About ACT

About ACTPsychological Inflexibility: An ACT View of Suffering and Failure to Thrive

The core conception of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) or (as it is usual called outside of a therapy context, Acceptance and Commitment Training ... also "ACT") is that psychological suffering and a failure to prosper psychologically is usually caused by the interface between the evolutionarily more recent processes of human language and cognition, and more ancient sources of control of human behavior, particular those based on learning by direct experience. Psychological inflexibility is argued to emerge from six basic processes. Stated in their most general fashion these are emotional inflexibility, cognitive inflexibility, attentional inflexibility, failures in perspective taking, lack of chosen values, and an inability to broaden and build habits of values-based action. Buttressed by an extensive basic research program on an linked theory of language and cognition, Relational Frame Theory (RFT), ACT takes the view that trying to change difficult thoughts and feelings in a subtractive or eliminative way as a means of coping can be counter productive, but new, powerful alternatives are available to deal with psychological events, including acceptance, cognitive defusion, mindful attention to the now, contacting a deeper "noticing" sense of self or "self-as-context", chosen values, and committed action. These six flexibility processes are argued to be inter-related aspects of psychological flexibility. Each of these in turn can be extended socially. For example, acceptance of emotions can extend to compassion for others; chosen values can extend to social values; a "noticing" sense of self to healthy social attachment; and so on.

The ACT Model

ACT is an orientation to behavior change and well-being that is based on functional contextualism as a philosophy of science, and behavioral and evolutionary science principles as expanded by RFT. As such, it is not a specific set of techniques or a specific protocol. ACT methods are designed to establish a workable and positive set of psychological flexibility processes in lieu of negative processes of change that are hypothesized to be involved in behavioral difficulties and psychopathology including

- cognitive fusion -- the domination of stimulus functions based on literal language even when that process is harmful,

- experiential avoidance -- the phenomenon that occurs when a person is unwilling to remain in contact with particular private experiences and takes steps to eliminate the form or diminish the frequency of these events and the contexts that occasion them, even when doing so causes psychological harm

- the domination of a conceptualized self over the "self as context" that emerges from perspective taking and deictic relational frames

- lack of values, confusion of goals with values, and other values problems that can underlie the failure to build broad and flexible repertoires linked to chosen qualities of being and doing

- inability to build larger and larger unit of behavior through commitment to behavior that moves in the direction of chosen values

and other such processes. Technologically, ACT uses both traditional behavior therapy techniques (defined broadly to include everything from cognitive therapy to behavior analysis), as well as others that are more recent "3rd wave" methods, and those that have largely emerged from outside the behavior tradition, such as cognitive defusion, acceptance, mindfulness, values, and commitment methods.

Research Support

Research seems to be showing that these methods are beneficial for a broad range of clients and positive psychological goals as well, not just in mental health areas but also in behavioral health, and social wellness areas. ACT teaches clients and therapists alike how to alter the way psychological experiences function rather than having to eliminate them from occurring at all. This empowering message has been shown to help clients cope with a wide variety of clinical problems, including depression, anxiety, stress, substance abuse, and even psychotic symptoms; to step up to the challenges of diet, sleep, exercise, or the behavioral challenges of physical disease; to help address social problems such as stigma or prejudice; or to seek positive outcomes in areas like relationships, cooperation, business, social justice, climate change, gender bias, and so on. The benefits are as important for the clinician as they are for clients. ACT has been shown empirically to alleviate therapist burnout, for example. By focusing on processes of change what began as a way of dealing with mental health issues is now a model that is used to understand and change human behavior more generally.

How Do You Learn and Apply ACT to Your Practice?

The list of resources below are a great, easy-to-access way to learn more about ACT, it's theoretical and philosophical background. We recommend checking out these pages, as they will provide an important foundation of knowledge. We've also compiled a list of ways to learn about ACT by reading ACT books, as well as getting consultation from others as you begin to apply the work to your work and practice. This additional list of resources will help you do so as well. ACBS members are strongly encouraged to join the ACT for Professionals email listserv. Once on that listserv you can ask virtually any question, or raise virtually any issue, and thousands of ACBS members will read it ... and you can almost be guaranteed of interesting and helpful responses. We've found that members of this listserv are nearly eight times more likely to remain as ACBS members over the years than those who are not on the listserv, and we think the reason is that listserv members come to appreciate the value of being part of a helpful and values-based knowledge development community. If you are not sure, join and lurk for a while. If you do not like it, it easy to step off later on -- you can do so with a single click in your membership dashboard.

Philosophical roots

Philosophical rootsFunctional Contextualism

ACT is rooted in the pragmatic philosophy of functional contextualism, a specific variety of contextualism that has as its goal the prediction and influence of events, with precision, scope and depth. Contextualism views psychological events as ongoing actions of the whole organism interacting in and with historically and situationally defined contexts. These actions are whole events that can only be broken up for pragmatic purposes, not ontologically.

Because goals specify how to apply the pragmatic truth criterion of contextualism, functional contextualism differs from other varieties of contextualism that have other goals. ACT thus shares common philosophical roots with constructivism, narrative psychology, dramaturgy, social constructionism, feminist psychology, Marxist psychology, and other contextualistic approaches, but its unique goals leads to different qualities and different empirical results than these more descriptive forms of contextualism, seeking as they do a personal appreciation of the complexity of the whole rather than prediction and influence per se.

ACT itself reflects its philosophical roots in several ways. ACT emphasizes workability as a truth criterion, and chosen values as the necessary precursor to the assessment of workability because values specify the criteria for the application of workability. Its causal analyses are limited to events that are directly manipulable, and thus it has a consciously contextualistic focus. From such a perspective, thoughts and feelings do not cause other actions, except as regulated by context.

Therefore, it is possible to go beyond attempting to change thoughts or feelings so as to change overt behavior, to changing the context that causally links these psychological domains.

Further information on functional contextualism is available here

Theoretical roots

Theoretical rootsRFT: A Theory of Language and Cognition

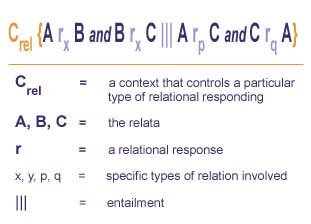

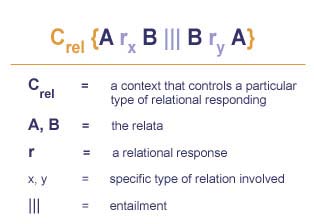

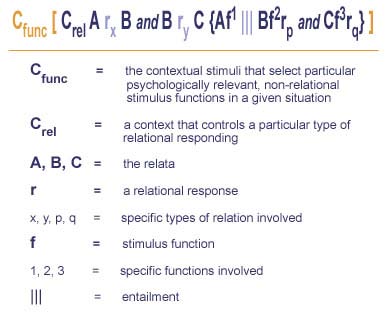

ACT is based on Relational Frame Theory (RFT), which is a comprehensive basic experimental research program into human language and cognition. RFT has become one of the most actively researched basic behavior analytic theories of human behavior, with over 70 empirical studies focused on it tenets. In ACT, virtually every component of the technology is connected conceptually to RFT, and several of these connections have been studied empirically.

According to RFT, the core of human language and cognition is the learned and contextually controlled ability to arbitrarily relate events mutually and in combination, and to change the functions of specific events based on their relations to others. For example, very young children will know that a nickel is larger than a dime by physical size, but not until later will the child understand that a nickel is smaller than a dime by social attribution. In addition to being arbitrarily applicable (a nickel is “smaller” than a dime merely by social convention), this more psychologically complex relation is mutual (e.g., if a nickel is smaller than a dime, a dime is bigger than a nickel), combinatorial (e.g., if a penny is smaller than a nickel and a nickel is smaller than a dime then a penny is smaller than a dime), and alters the function of related events (if a nickel has been used to buy candy a dime will now be preferred even if it has never actually been used before).

The applied implications of RFT derived from the following key features:

- Human language and higher cognition is a specific kind of learned behavior. RFT researchers have shown that arbitrarily applicable comparative relations (the nickel and dime situation just mentioned) can be trained as an overarching operant in young children; similar evidence has emerged with frames of opposition and coordination.

- Relational frames alters the effects of other behavioral processes. For example, a person who has been shocked in the presence of B and who learns that B is smaller than C, may show a greater emotional response to C than to B, even though only B was directly paired with shock

- Cognitive relations and cognitive functions are regulated by different contextual features of a situation.

The primary implications of RFT in the area of psychopathology and psychotherapy extend from the three features just described. RFT argues that:

- verbal problem solving and reasoning is based on some of the same cognitive processes that can lead to psychopathology, and thus it is not practically viable to eliminate these processes,

- much as extinction inhibits but does not eliminate learned responding, the common sense idea that cognitive networks can be logically restricted or eliminated is generally not psychologically sound because these networks are the reflection of historical learning processes;

- direct change attempts focused on key nodes in cognitive networks creates a context that tends to elaborate the network in that area and increase the functional importance of these nodes, and

- since the content and the impact of cognitive networks are controlled by distinct contextual features, it is possible to reduce the impact of negative cognitions whether or not they continue to occur in a particular form. Taken together, these four implications mean that it is often neither wise nor necessary to focus primarily on the content of cognitive networks in clinical intervention. Fortunately, the theory suggests that it is quite possible instead to focus on their functions.

RFT has proven itself successful so far in modeling higher cognition in a number of areas, and the neurobiological data collected so far comport with the theory. RFT is meant to be a comprehensive contextualistic account of human language and cognition and thus its goals extend far beyond ACT or even the behavioral and cognitive therapies in general. Because all of the key features of the theory are cast in terms of manipulable contextual variables, it has readily lead to applied interventions in such areas as education.

Theory of Psychopathology

Theory of PsychopathologyCore Problem Processes

From an ACT / RFT point of view, while psychological problems can emerge from the general absence of relational abilities (e.g., in the case of mental retardation), a primary source of psychopathology (as well as a process exacerbating the impact of other sources of psychopathology) is the way that language and cognition interact with direct contingencies to produce an inability to persist or change behavior in the service of long term valued ends. This kind of psychological inflexibility is argued in ACT and RFT to emerge from weak or unhelpful contextual control over language processes themselves, and the model of psychopathology is thus linked point to point to the basic analysis provided by RFT. This yields an accessible and clinically useful middle level theory bound tightly to more abstract basic principles.

A core process that can lead to pathology is cognitive fusion, which refers to the domination of behavior regulatory functions by relational networks, based in particular on the failure to distinguish the process and products of relational responding. In contexts that foster such fusion, human behavior is guided more by relatively inflexible verbal networks than by contacted environmental contingencies. This is fine in some circumstances, but in others it increases psychological inflexibility in an unhealthy way. As a result, people may act in a way that is inconsistent with what the environment affords relevant to chosen values and goals. From an ACT / RFT point of view, the form or content of cognition is not directly troublesome, unless contextual features lead this cognitive content to regulate human action in unhelpful ways.

The functional contexts that tend to have such deleterious effects are largely sustained by the social / verbal community. There are several. A context of literality treats symbols (e.g., the thought, “life is hopeless”) as one would referents (i.e., a truly hopeless life). A context of reason-giving bases action or inaction excessively on the constructed “causes” of one's own behavior, especially when these processes point to non-manipulable “causes” such as conditioned private events. A context of experiential control focuses on the manipulation of emotional and cognitive states as a primary goal and metric of successful living.

Cognitive fusion supports experiential avoidance -- the attempt to alter the form, frequency, or situational sensitivity of private events even when doing so causes behavioral harm. Due to the temporal and comparative relations present in human language, so-called “negative” emotions are verbally predicted, evaluated, and avoided. Experiential avoidance is based on this natural language process – a pattern that is then amplified by the culture into a general focus on “feeling good” and avoiding pain. Unfortunately, attempts to avoid uncomfortable private events tend to increase their functional importance – both because they become more salient and because these control efforts are themselves verbal linked to conceptualized negative outcomes – and thus tend to narrow the range of behaviors that are possible since many behaviors might evoke these feared private events.

The social demand for reason giving and the practical utility of human symbolic behavior draws the person into attempts to understand and explain psychological events even when this is unnecessary. Contact with the present moment decreases as people begin to live “in their heads.” The conceptualized past and future, and the conceptualized self, gain more regulatory power over behavior, further contributing to inflexibility. For example, it can become more important to be right about who is responsible for personal pain, than it is to live more effectively with the history one has; it can be more important to defend a verbal view of oneself (e.g., being a victim; never being angry; being broken; etc) than to engage in more workable forms of behavior that do not fit that that verbalization. Furthermore, since emotions and thoughts are commonly used as reasons for other actions, reason-giving tends to draw the person into even more focus on the world within as the proper source of behavioral regulation, further exacerbating experiential avoidance patterns. Again psychological inflexibility is the result.

In the world of overt behavior, this means that long term desired qualities of life -- values -- take a backseat to more immediate goals of being right, looking good, feeling good, defending a conceptualized self, and so on. People lose contact with what they want in life, beyond relief from psychological pain. Patterns of action emerge and gradually dominate in the person’s repertoire that are detached from long term desired qualities of living. Behavioral repertoires narrow and become less sensitive to the current context as it affords valued actions. Persistence and change in the service of effectiveness is less likely.

Quick & Dirty ACT Analysis of Psychological Problems

Quick & Dirty ACT Analysis of Psychological Problems- Most psychological difficulties have to do with the avoidance and manipulation of private events.

- All psychological avoidance has to do with cognitive fusion and its various effects.

- Conscious control belongs primarily in the area of overt, purposive behavior.

- All verbal persons have the “self” needed as an ally, but some have run from that too.

- Clients are not broken, and in the areas of acceptance and defusion they have the psychological resources they need if they can be harnessed.

- To take a new direction, we must let go of an old one. If a problem is chronic, the client's solutions are probably part of them.

- When you see strange loops, inappropriate verbal rules are involved.

- The value of any action is its workability measured against the client's true values (those he/she would have if it were a free choice). The bottom line issue is living well, not having small sets of “good” feelings.

- Two things are needed to transform the situation: accept and move.

The Six Core Processes of ACT

The Six Core Processes of ACTThe Psychological Flexibility Model

The general goal of ACT is to increase psychological flexibility – the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behavior when doing so serves valued ends. Psychological flexibility is established through six core ACT processes. Each of these areas are conceptualized as a positive psychological skill, not merely a method of avoiding psychopathology.

Acceptance

Acceptance is taught as an alternative to experiential avoidance. Acceptance involves the active and aware embrace of those private events occasioned by one’s history without unnecessary attempts to change their frequency or form, especially when doing so would cause psychological harm. For example, anxiety patients are taught to feel anxiety, as a feeling, fully and without defense; pain patients are given methods that encourage them to let go of a struggle with pain, and so on. Acceptance (and defusion) in ACT is not an end in itself. Rather acceptance is fostered as a method of increasing values-based action.

Cognitive Defusion

Cognitive defusion techniques attempt to alter the undesirable functions of thoughts and other private events, rather than trying to alter their form, frequency or situational sensitivity. Said another way, ACT attempts to change the way one interacts with or relates to thoughts by creating contexts in which their unhelpful functions are diminished. There are scores of such techniques that have been developed for a wide variety of clinical presentations. For example, a negative thought could be watched dispassionately, repeated out loud until only its sound remains, or treated as an externally observed event by giving it a shape, size, color, speed, or form. A person could thank their mind for such an interesting thought, label the process of thinking (“I am having the thought that I am no good”), or examine the historical thoughts, feelings, and memories that occur while they experience that thought. Such procedures attempt to reduce the literal quality of the thought, weakening the tendency to treat the thought as what it refers to (“I am no good”) rather than what it is directly experienced to be (e.g., the thought “I am no good”). The result of defusion is usually a decrease in believability of, or attachment to, private events rather than an immediate change in their frequency.

Being Present

ACT promotes ongoing non-judgmental contact with psychological and environmental events as they occur. The goal is to have clients experience the world more directly so that their behavior is more flexible and thus their actions more consistent with the values that they hold. This is accomplished by allowing workability to exert more control over behavior; and by using language more as a tool to note and describe events, not simply to predict and judge them. A sense of self called “self as process” is actively encouraged: the defused, non-judgmental ongoing description of thoughts, feelings, and other private events.

Self as Context

As a result of relational frames such as I versus You, Now versus Then, and Here versus There, human language leads to a sense of self as a locus or perspective, and provides a transcendent, spiritual side to normal verbal humans. This idea was one of the seeds from which both ACT and RFT grew and there is now growing evidence of its importance to language functions such as empathy, theory of mind, sense of self, and the like. In brief the idea is that “I” emerges over large sets of exemplars of perspective-taking relations (what are termed in RFT “deictic relations”), but since this sense of self is a context for verbal knowing, not the content of that knowing, it’s limits cannot be consciously known. Self as context is important in part because from this standpoint, one can be aware of one’s own flow of experiences without attachment to them or an investment in which particular experiences occur: thus defusion and acceptance is fostered. Self as context is fostered in ACT by mindfulness exercises, metaphors, and experiential processes.

Values

Values are chosen qualities of purposive action that can never be obtained as an object but can be instantiated moment by moment. ACT uses a variety of exercises to help a client choose life directions in various domains (e.g. family, career, spirituality) while undermining verbal processes that might lead to choices based on avoidance, social compliance, or fusion (e.g. “I should value X” or “A good person would value Y” or “My mother wants me to value Z”). In ACT, acceptance, defusion, being present, and so on are not ends in themselves; rather they clear the path for a more vital, values consistent life.

Committed Action

Finally, ACT encourages the development of larger and larger patterns of effective action linked to chosen values. In this regard, ACT looks very much like traditional behavior therapy, and almost any behaviorally coherent behavior change method can be fitted into an ACT protocol, including exposure, skills acquisition, shaping methods, goal setting, and the like. Unlike values, which are constantly instantiated but never achieved as an object, concrete goals that are values consistent can be achieved and ACT protocols almost always involve therapy work and homework linked to short, medium, and long-term behavior change goals. Behavior change efforts in turn lead to contact with psychological barriers that are addressed through other ACT processes (acceptance, defusion, and so on).

Taken as a whole, each of these processes supports the other and all target psychological flexibility: the process of contacting the present moment fully as a conscious human being and persisting or changing behavior in the service of chosen values. The six processes can be chunked into two groupings. Mindfulness and acceptance processes involve acceptance, defusion, contact with the present moment, and self as context. Indeed, these four processes provide a workable behavioral definition of mindfulness (see the Fletcher & Hayes, in press in the publications section). Commitment and behavior change processes involve contact with the present moment, self as context, values, and committed action. Contact with the present moment and self as context occur in both groupings because all psychological activity of conscious human beings involves the now as known.

A Definition of ACT

ACT is an approach to psychological intervention defined in terms of certain theoretical processes, not a specific technology. In theoretical and process terms we can define ACT as a psychological intervention based on modern behavioral psychology, including Relational Frame Theory, and evolutionary science, that applies mindfulness and acceptance processes, and commitment and behavior change processes, to the creation of psychological flexibility.

ACT Video Series - Six Core Processes of ACT

ACT Video Series - Six Core Processes of ACTThe Veterans Health Administration, part of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, has a video series about ACT that provides an introduction to the six core processes of ACT.

ACT Therapeutic Posture

ACT Therapeutic Posture- Whatever a client is experiencing is not the enemy. It is the fight against experiencing experiences that is harmful and traumatic.

- You can't rescue clients from the difficulty and challenge of growth.

- Compassionately accept no reasons—the issue is workability not reasonableness.

- If the client is trapped, frustrated, confused, afraid, angry or anxious be glad—this is exactly what needs to be worked on and it is here now. Turn the barrier into the opportunity.

- If you yourself feel trapped, frustrated, confused, afraid, angry or anxious be glad: you are now in the same boat as the client and your work will be humanized by that.

- In the area of acceptance, defusion, self, and values it is more important as a therapist to do as you say than to say what to do

- Don't argue. Don't persuade. The issue is the client's life and the client's experience, not your opinions and beliefs. Belief is not your friend.

- You are in the same boat. Never protect yourself by moving one up.

- The issue is always function, not form or frequency. When in doubt ask yourself or the client “what is this in the service of.”

Readings on this topic

Follette, V. M., & Batten, S. V. (2000). The role of emotion in psychotherapy supervision: A contextual behavioral analysis. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 7(3), 306-312.

Pierson, H. & Hayes, S. C. (2007). Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to empower the therapeutic relationship. Chapter in P. Gilbert & R. Leahy (Eds.), The Therapeutic Relationship in Cognitive Behavior Therapy (pp. 205-228). London: Routledge.

Wilson, K. G., & Sandoz, E. K. (2008). Mindfulness, values, and the therapeutic relationship in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. In S. F. Hick & T. Bein (Eds.), Mindfulness and the therapeutic relationship. New York: Guilford Press.

ACT Therapeutic Steps

ACT Therapeutic Steps- Compassionately confront the unworkable agenda, appealing always to the client's experience as the ultimate arbiter

- Support the client in feeling and thinking what they directly feel and think already—as it is not as what it says it is—and to find a place from which that is possible.

- In the service of that goal, teach acceptance and defusion skills.

- Help the client make a richer and less defended contact with the present moment, and with their own on-going thoughts, feelings, and sensations.

- Help the client contact a transcendent sense of self.

- Help the client become more consistently mindful.

- Help the client move in a value direction, with all of their history and automatic reactions.

- Help the client detect traps, fusions, and strange loops.

- Repeat, expand the scope of the work, and repeat again, until the clients generalizes.

- (and don't believe a word you are saying).

Common Misunderstandings About ACT / RFT

Common Misunderstandings About ACT / RFTHere are a number of common misunderstandings about ACT and RFT and CBS. I've listed only ones that I think are demonstrably false. Ones that could be true I have not listed since this page is about misunderstandings, not legitimate weaknesses. Comments follow each. If you know of others, let me know - Steven Hayes

- ACT is just _____ (fill in your favorite: Buddhism, CT, BT, CBT, Logotherapy, a psychology of the will, Gestalt, existential, est, Morita, constructive living, solution focused therapy, Kelly role therapy, and so on and so on)

Resemblance is a fun game to play but I have yet to have anyone say these things in strong form (it is just _____) when they have really delved into the philosophy, theory, data, and technology. It is actually a positive sign when you see that others are pointing to somewhat similar issues. If multiple paths lead in a direction perhaps that is a direction worth exploring. If folks want to draw the connections above, it would be good to do them seriously and in print so people can understand the connections. The only ones I could see myself fully agreeing to is "ACT is just behavior analysis" ... or, properly understood, "ACT is just behavior therapy," but I'd quickly want to add "but that area itself has to be understood in a different way to say that." As far as roots, some of these are indeed influences on ACT. You could find some historical connections with CT, BT, CBT, Logotherapy, Gestalt, existential, and est for example. Maybe Buddhism if you mean "estern thought" -- as a child of the 60's it would be hard to avoid that. Probably a few more and as it expands lots of new things come in. ACT is a vast community now. - ACT is a cult

James Herbert has a great powerpoint on this site walking through why that comparison is unfair and inaccurate. Cults are closed off; they avoid criticism; they are hierarchical; they suppress open expression. ACBS is the exact opposite in all of these areas. - ACT is just the latest fad

ACT will ultimately die, as will we all, and it may indeed do so in a matter of decades or sooner, as what is worthwhile inside it become better understood and enters into the mainstream (that process of assimilation is happening at light speed right in front of our eyes), but if you mean that it is frivolous or insubstantial, that is just factually incorrect. When you last 35 years, do over 1000 basic and applied studies, and train over 50,000 people, "fad" is just not an applicable term. Is it? Inside the ACBS community we suspect that the applied and basic theory underlying ACT and RFT (etc) is wrong but that is because so far in science all theories have ultimately been shown to be incorrect. We just don't know where it is wrong yet ... but we are chasing that rabbit! Come help us prove ourselves wrong! - ACT is new on the scene

It is just under 35 years old. The first ACT workshop was given in 1982 at Broughton Hospital in North Carolina. - ACT is old on the scene and thus its outcome studies should be __ times more

When I first posted this page in the early 2000s I had to explain our slow start, but now the criticism is just so far out of date even that explanation seems unneeded. OK, here is the explanation I used to give: ACT followed a different development path linked to philosophy, basic research, and process measurement. There was a 14 year gap in outcome studies from 1986 to 2000. That gap should not be held against the tradition because the detour was linked to even higher standards and goals. During that time, functional contextualism, the psychological flexibility model, RFT, measures of psychological flexiblity, and a contextual behavioral science approach were created -- and it seemed responsible to do that before larding up with RCTs after the first 3 successful ones in the mid 1980s. ACT is willing to be held to RCT-linked standards but RCTs alone are not enough to create a progressive field. You need a theory and development strategy that works. Once we had that better worked out we did indeed come back to outcome studies. If you look at the outcome studies since 2000 it would be a hard case to make that ACT does not care about outcome data. In 2000 there were 3 RCTs in ACT but it began to pick up in the mid 2000s. When I first rewrote this page as 2011 began it was up to 37 RCTs. Wow. Now it is five years later and I'm rewriting the page again in early 2016. The number of RCTs is hard to say precisely because a new one appears every week or less and no one can keep up anymore and still have a life. My best guess is that it is sliding past 200 (I have 153 in a file but a new paper my students wrote for a class tells me that there are about 70 more studies I missed that are not in English). And meanwhile ACT has more and more consistent mediation outcomes than any approach in existence. Our guess is over 50 studies. And it is the ONLY psychotherapy with a vigorous basic science of cognition underneath it, with hundreds of studies on RFT. An entire book has been written on the ACT Research Journey (Hooper & Andersson, 2015: http://www.amazon.com/Research-Journey-Acceptance-Commitment-Therapy/dp/1137440163/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1459110186&sr=1-1&keywords=ACT+research+journey). So, really, anyone suggesting we are slack in terms of research just does not know what he or she is talking about. Counting all areas of CBS my best guess based on search engines is that there are over 2000 studies if you apply a liberal set of search criteria and about 1000 if you apply a strict set. - ACT seeks ridiculously high goals and thus is making grandiose predictions or claims. Aspirations are not predictions or claims. Seeking a comprehensive account of behavior that would apply to all human action has always been the goal of behavior analysis as is shown in things such as Walden II. Why is a grand aspiration grandiose?

- ACT works only with the well-educated

There are many trials indicating ACT is helpful for those who are poor, uneducated, intellectually disabled, children, those diagnosed with psychotic disorders, and so on and on. This criticism comes because the theory can be hard to understand (especially RFT). But we do not teach theory to client, we do therapy. That is different. - ACT works only for white middle class Americans

There are ACT studies from 15 countries includinging countries in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Successful studies have been done with poor urban black populations; unemployed poor Asian American populations; institutionalized South African blacks, etc. As of early 2016 there are 45 RCTs done on ACT in Iran; over 30 RCTs in Korea. The outcomes are equally good. The criticism is simply invalid. - ACT is not committed to science

Come on; wake up. Put in key ACT and RFT terms into the Web of Science or Google Scholar and look at what is out there dude. Download the studies. It after you do all that you repeat this claim that within arm's reach of me or you'd better be able to duck fast. - The ACT research base is weak

ACT has drawn a lot of interest from funded researchers and ACT funded studies are as good as any out there. There are a lot of them too (perhaps 50 RCTs of that kind) and the outcomes are often (not always) impressive. Yes, in some areas the research base is lean -- but ACT is not just for one problem area. In some areas, such as smoking or chronic pain, you'd have to distort the meaning of evidence to say that they ACT research base is weak. And these are areas where people have worked for years to dial in how to move ACT processes. So overall the research base seems impressive given the scope of ACT work. Having said that, we need to add three things. First, ACT draws a lot of interest from students, the developing world, or parts of the developed world without a grant infrastructure. These studies often have methodological issues (sample size; controls; etc) but jeez, how do they DECREASE what we know if they ADD to what we know from the best studies? Can someone please explain that to me? It happens IMHO only if people doing meta-analyses average methodology ratings. I'm sorry, that is just a dumb idea. Sure, weight findings study by study in light of methodological issues. But if a person in Liberia shows that ACT is helpful for problem x, and a huge grant-based study at a Western academic medical center with all of the bell and whistles showed that ACT is helpful for that same problem, the one in Liberia added to what we know regardless of its weaknesses. It showed that these approaches to not just apply to the western world, for one thing. It is fine to use the well controlled one to estimate effect sizes. But don't average the methodology ratings from the two and then say that the overall knowledge is weak in problem area x because the average methdology score is humble. Aaaagh. That is just stupid. Second, you need a string of studies in a given area with a given population to learn how to move psychological flexibility processes. If the technology has weak outcomes but did not move the processes, that is an unfortunate technology error, not a model failure. If you move the processes and the outcomes are poor that is a model failure. Yes, there are technology failures in ACT, but usually with new populations, settings, or modes of delivery. I know of no replicated model failures in 35 years of ACT / RFT / CBS research. Finally, some meta-analyses are biased. They are. Look at the overall pattern of meta-analyses and look carefully for responses to meta-analyses. For example, Ost claimed in 2008 that 13 ACT RCTs were weaker than 13 matched CBT RCTs; but then Gaudiano showed that effect was 100% due to grant funding, and furthermore 12 of the 13 ACT studies published mediational outcomes while 1 of the 13 CBT studies did so. An objective reader should reject Ost's comparison. You have to look at the criteria too. For example, if you rightly put "well defined population" on a list of methodological criteria, and then in small print insist on a DSM diagnosis as the only metric for a "well defined population," ACT will look methodologically weaker due to intellectually defensible choices that the reader might not realize is at play. CBS researchers generally despise the DSM. Including such a scoring approach behind an item will lead to a biased "criterion" (one that even NIMH has abandoned!). But the reader has to dig deep to sniff out bias liek that when it is there -- and sometimes not matter how much care, the reader will be bamboozled (e.g., if the ratings themselves have horrible kappas that are not reported). But the ACT community does not lay back on such things. We keep asking for the information and we keep trying to understand findings. As a reader: Keep your powder dry; be careful before leaping; look at the entire set of criticisms, responses, and meta-analyses; use your best judgment. - ACT is just a technology

It is a far more ... do your reading. It is a model linked to a philosophy, basic science, and a strategy of development. - ACT is just a philosophy

Ditto. - ACT is just acceptance

Ditto. - ACT is just commitment

Ditto. - ACT is just acceptance and commitment

Aw, come on. This kind of thing comes from folks reading the titles of books and studies instead of books and studies. - Acceptance is important because it is a way to change the content of emotion (so ACT is really about that)

The data suggest otherwise. Emotion do often change, but that change predicts behavioral outcomes more poorly than changes in the functions of emotions -- and sometimes good outcomes come without a change in emotion within the extant ACT literature. - Defusion is important because it is a way to change the content of thought (so ACT is really about that)

Double ditto. Same point. Also decent data supporting it. Will thoughts change? Sure! RFT is all about changing thoughts and of course ACT changes thoughts. - The ACT model of cognition is no different than any CBT model -- it is just different in its terminology

If you believe that, have the courage to do your homework in detail and write it up in article form. Then be prepared to have others go after your ideas. We have so far responded to every single serious criticism in print in ACT or RFT, so anyone can read the criticisms and the response and judge the arguments. So far no one, I mean no one, has made the claim above in a careful scholarly article. But it is not the ACT world's obligation to prevent the claim from being made in the hallways of convention hotels or on listserves. Even here we do what we can, however. You are reading exhibit A in that area. - Defusion is just distancing as that concept is used in CT

They are indeed related. That is one of the real historical sources of ACT. But in ACT there are scores of such techniques, the are emphasized a great deal, and they are put to a quite different purpose than in traditional CT. - ACT is just mindfulness as that concept is used by Buddhists or ______ (fill in the blank)

ACT is clearly broader at the level of theory and technology. Mindfulness is itself a broad term that ican be vague if it is left at that level. That is why we have written 4-5 articles walking through the concept of mindfulness and trying to come up with a tighter analysis of it. When defined in the right way, ACT is a mindfulness-based approach but it is more than that as well. - Defusion is just exposure in a traditional sense

Research shows that defusion supports exposure. If you say it is exposure then you have expanded exposure to conver most contact of human beings with events and that is troublesome. Besides exposure itself is not well understood, and ACT folks have a flexibility and pattern-based account of exposure that comports with the ACT model. - Acceptance is just exposure in a traditional sense

Research shows that it supports exposure and appears to empower the impact of exposure. ACT is an exposure-based technology and we said in the first chapter on ACT in 1987. But the ACT view of exposure is that it is organized contact with previously repertorie narrowing events for the purpose of creating response flexibility. That is why our goal is teaching more flexible contact with private events and more flexible patterns of responding. We want patients to be able to label emotions; to feel them openly; and to be able to approach their values in action. The most recent work in traditional exposure in CBT is finally catching up that approach. We do not do exposure to reduce emotions (thought they usually are reduced) -- but it turns out that is not why exposure works even in traditional CBT. - ACT does not care about the relationship

We have a model of it; we teach it; we emphasize it. We have data showing that ACT gets high aliance scores; they predict outcome; but they are themselves explained in part by changes in acceptance/defusion/valued action. So no only do we care about the relationship, we care enough to be able to teach clinicans how to create powerful ones: create a psychologically flexibile relationship. - ACT eschews meditation and contemplative practice

Contemplative practice is often in our protocols (about 40% of the RCTs); Guided meditations is in nearly 100% of the protocols; ACT targets mindfulness at the level of process in multiple ways; it moves and is mediated by these processes; psychological flexibility impacts the brain or telomere length (etc) similarly. Now if you insist that mindfulness = sitting and following the breath, yes ACT is mostly not that. But if you insist on that narrow definition you now have to go to war with ancient mindfulness traditions too. Is a koan about mindfulness? Is chanting? This is why I resisted the word "mindfulness" in early ACT writing. I did not want to enter into arguments that were thousands of years old. ACT cares about mindfulness as a process. - You should not mix behavioral procedures with ACT

The model says you should. ACT is part of behavior therapy. With all due respect, you don't get to peel it away from its model just because that makes you uncomfortable in your sorting of things into cubby holes. - If you do mix behavioral procedures with ACT you now have a combined treatment

ACT is a model. Since the model says you should do this, it does not become a combination treatment to follow the model. In early ACT work we often deliberately hobbled the model so we could be heard by others (e.g., taking out formal exposure in studies on OCD). Times up. After 200 RCTs, no more hobbling the model to avoid science critics and their cubby holes. - The other aspects of ACT add nothing to the behavioral elements

We know that these other elements are helpful and that they can support the behavioral elements. If you mean that the other elements are inert, that is clearly untrue. We published a meta-analysis of the first 60 or so component studies and all of the components matter [Levin, M. E., Hildebrandt, M. J., Lillis, J., & Hayes, S. C. (2012). The impact of treatment components suggested by the psychological flexibility model: A meta-analysis of laboratory-based component studies. Behavior Therapy, 43, 741–756. DOI: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.05.003.] More formal component analysese are beginning to appear [Villatte, J. L., Vilardaga, R., Villatte, M., Vilardaga, J. C. P., Atkins, D. A., & Hayes, S. C. (2016). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy modules: Differential impact on treatment processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 77, 52-61. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.001]. And we know that all of the aspects of the psychological flexibility model contribute to outcomes (McCracken and colleagues have a study on that in the chronic pain area). - The data on traditional CBT is far stronger

Well, duh. Your father's retirement account is bigger than yours too. ACT is part of the CBT / BT / BA family but its specific research program takes a large community to mount. The CBS community is focused on basic science, processes of change, micro-studies, prevention, social change, link to evolution science, and so on and on. But dig deeper. The vast majority of what is specifically supported in traditional CBT is stuff that ACT folks agree with anyway. If you insist on drag race studies --OK. Be patient. But you can't start outcomes studies in 2000 and expect 16 years later to have the same amount of data as the biggest dog on the block. But our research productivity is now obvious for anyone to see. If you know how to de searches - It is surely safe to mix ACT techniques with other techniques I'm more comfortable with while I wait passively to understand the model

Ah, no. Down that path lies chaos. It is such a poor model of scientific development. Understand first. Get the data. Then add anything that makes sense for good theoretical and practical reasons, not just because you feel like it. One great benefit we have in ACT: if the thinks you like to do already improve psychological flexibility (measure it regularly) than by all means include those things. - When I do that I should be able to rename it and get famous tomorrow because what I added (here you can pick any of the other misunderstandings -- relationship, emotion, mindfulness, etc etc) is obviously missing from the model

You can rename it and still come and talk at our conventions etc. We don't care about names. Some folks in the CBS community call ACT "Acceptance Based Behavior Therapy" for example. It turns out that psychological flexibility still mediates the outcomes. But branding helps people find the work so at least rename it for a good reason (e.g., sometimes it make it hard to do meta-analysises). It's up to you. - You can mix ACT with the cognitive elements of CT / CBT easily

With some, but be careful. Incoherence is not usually helpful and patients will detect the incoherence if it is there. - It is safe to do research on ACT without doing any training in ACT

Is it safe to do surgery that way? You cannot read a book and do this well. Get some training. It is cheap and available and non-proprietary. ACT folks will collaborate and consult. Reach out. - It is safe to criticize ACT based on what you've heard about it from others who are not expert in it

What is it about reading carefully that is so aversive? - ACT contains nothing new

If you've studied it thoroughly, just say it in print and say why you say that and let us all look at it dispassionately. If you've not done your homework yet, see above. - ACT is behavioral in an S-R sense

ACT is actively hostile to S-R psychology. - ACT is behavioral in a traditional behavior analytic sense

ACT / RFT is part of behavior analysis, but RFT changes everything. ACT is part of post-Skinnerian behavior analysis -- which is a new form. We call it "contextual behavioral science." Read the RFT book for why we say that. - For these reasons ACT is not oriented toward cognition

200 studies on cognition later, how can folks still say that?! Come to a training at least. - For these reasons ACT is not oriented toward emotion

Come to a training! Watch some tapes! Go look at my TEDx talk: www.bit.ly/StevesFirstTED - Because ACT is broadly applicable it is primarily based on a non-specific clinical process

The theory says why it is broadly applicable and the process data so far say it is successful due to specific process changes. We now have socres of mediational analyses out or in press. - Anything that works for such a broad range of problems must be bulls**t

The theory says why it is broadly applicable. Who are you to say a priori what nature is like? - There are not many outcome studies on ACT

About 200 RCTs and scores more controlled time series designs and counting. - ACT / RFT is a small minority

Maybe. But there are about 3000 folks on the ACT / RFT listservs and over 8000 in the association. ACBS is bigger than ABCT or ABAI. Its one of the the fastest growing associations of its kind out there. Besides, minority or not, we are speaking of ideas and data, not politics. - ACT proponents make excessive claims that go beyond the data

A quote would be nice. - ACT is hierarchical and you have to pledge allegiance to a leader to be involved with it

It's an open list serve; an open website; no certification of therapists; no cut goes to originators from members/trainers/etc; you can get our protocols for free; anyone can become a trainer. There are more ACT books by others than by the originators, by far. This is just so unfair. Its a cartoon, and an ignorant one at that. - ACT processes have not been studied

Download the list of studies and read them. We think our process data are stronger than just about any other approach in all of applied psychology, and our link to basic science is excellent. - RFT can't explain anything other models of cognition cannot explain

RFT researchers have explained phenomena that other approaches have had hard times with. For example, we are learning how to establish a sense of self, we know a lot about how metaphor works, we know a core process in human cognition. And it appears that RFT programs raise IQs more dramatically than anything else out there; it helps with acquisition of language in disabled children; it has better implicit measures than anyone; it can predict who will succeed for fail clinically; etc. - RFT is just jargon

How much have you carefully read so far? Until you read carefully you cannot distinguish jargon and a technical language. RFT has a techical language, but only when technical terms are needed. If you disagree, pick a technical term and show how it is the same as a common sense one. Maybe there was a slip. - ACT is just jargon

Same reaction as above. - No one can understand RFT

Do the RFT tutorial on this website. Yes the basic studies are damn hard to understand ... you are languaging about language and that is just confusing. But it is not beyond anyone reading this website. Physics is hard too -- so? - No one can understand ACT

You can. And "understanding" in a purely intellectual sense is not the point for clients anyway. Usually what therapists mean when they say this is that they are afraid that if they don't understand it thoroughly they can't do it effectively. Folks like Raimo Lappalainen have shown that ACT works even when delivered by beginning therapists who don't really understand it. In fact most of the outcome data on ACT was not done with experienced ACT therapists. It's a miracle these studies work at all -- but they do. Understanding does help: we have studies - RFT has little to do with ACT

ACT and RFT co-evolved. There are many, many links are there and in both directions. It is not a matter of point to point correspondence and it should not be if we are right and applied and basic science should relate in a reticulated way. - ACT folks don't want CT people to be involved and they look down on them

Ask some CT people who got involved in ACT work what they think about how they were treated. Just ask. - We don't know which components work because there are no dismantling studies

ACT comes from an inductive tradition. Rather than wait decades for dismantling studies we've done over 60 technique building and micro-analytic studies (see the reference above) and every aspect of the model has at least some targetted research data. And we do have some studies that dismantle the methods to a degree (an example was listed above) - I hate the enthusiasm of students who do these workshops -- it scares me

We can all agree that enthusiasm is not the same as substance ... but suppose that enthusiasm is hostile to substance? Besides this concern itself sounds emotional so why let emotions substitute for data just because it is now your emotions we are talking about (it scares me) ? Be consistent. If enthusism creeps you out, try to make room for being creeped out, hang on to your legitimate skepticism, and follow the data. - I just don't like ACT

See above. - Talk of spirituality in ACT is creepy

It is treated as a naturalistic concept. ACT is not a religion. - I don't want to be told my values

ACT folks will never do that ... your values are your choice. - There is no data on ACT in groups

About a third of the RCTs on ACT are done in groups, so that means scores of studies. - ACT works through the same process as ____ (fill in your favorite)

Show me the actual research please. The reverse is much more likely to be true so far (the psychological flexibility model explains your favorite). But that is cool, no? Now that we know how things work we can chase the outcomes together. - ACT is not self-critical

Lurk on the list serve and see. Come to a WorldCon and see. - Steve Hayes is a jerk -- I saw him do a mean joke or a mean comment at ABCT or ABAI

ACT is not Steve Hayes -- there are scores of leaders in ACT / RFT. Besides, distinguish the message from the messenger. Some of us are confrontational about intellectual issues, but we don't go after people or traditions: just ideas. The list serve NEVER has flame wars, and that includes toward others. We are just playing hard. Why not? It is fun and can be helpful. Not everyone inside CBS plays the same way. if you hate folks who like to argue, go to ACT talks (etc) by softer folks. As for mean humor, sometimes roast humor can slip across the line a bit, but we tease those we respect. In the ACT community we use humor to remind us all that this work is not about the muckity mucks (including those inside ACBS) ... it is a shared enterprise and everyone is part of it who wants to be part and is willing to bring science based values and caring to the table. If you come to an ACBS conference you will see that the ACT / RFT leadership is outright ridiculed in the "follies" and it is just great fun. Anyone has access to the stage. Even cognitive therapists! : ) - ACT is crazy (or my personal favorite variant since I'm writing this, Steve is crazy)

Ah, finally you are getting somewhere. But as that Time guy said in 2006 in the last line of the story on me and on ACT -- we may just be crazy enough to pull it off. If you are nutty enough to want to help us, come help us succeed!

Criticisms of ACT

Criticisms of ACTGiven the values of ACBS, there has been efforts from the beginning of the ACBS community to encourage responsible criticism, to give thoughtful critics a stage to speak to the group, of trying to respond thoughtfully in writing to knowledgeable critics, and of trying to resolve issues empirically where possible. Criticisms of ACT have appeared in published forms. The written criticisms of RFT (and to a lesser degree, functional contextualism) are extensive and in writing, as are the defenses. They can be found in the other sections of the website.

Self-Criticism

Part of the core of the ACT / RFT tradition is the openness to criticism, including self-criticism. At the LaSalle ACT Summer Institute (Philadelphia, 2005) James Herbert gave a really solid paper walking through many of the criticisms he knew about, under the title "Is ACT a fad?" He considers not just whether the criticisms are correct, but what those in the ACT / RFT community should do about them. You can look at that talk by clicking on the link below.

- Criticisms of ACT, ACT Summer Institute II (July 2005, PowerPoint file)

Published Criticisms and Responses: An Ongoing Conversation Below is a list of papers that have been published criticizing ACT as well as replies that have been published when available. If you know of other criticisms or replies please email us or add a child page to this page.

- Corrigan, P. (2001). Getting ahead of the data: A threat to some behavior therapies. The Behavior Therapist, 24(9), 189-193.

This was the first strong criticism of ACT published. Corrigan argued that the ratio of non-empirical to empirical articles could be used to argue that third-wave CBT was ahead of its data.

A reply: Hayes, S. C. (2002). On being visited by the vita police: A reply to Corrigan. The Behavior Therapist, 25, 134-137.

The reply argued that the ratio of non-empirical to empirical articles could not be meaningfully used as a measure of getting ahead of data since there were many good reasons to write theoretical discussion pieces. Instead, actual claims that got ahead of the data had to be identified and none have been. Pat has been helpful to ACT researchers in various capacities over the years since that article.

- Corrigan, P. (2002). The data is still the thing: A reply to Gaynor and Hayes. The Behavior Therapist, 25, 140.

- Asmundson, G. J. G., & Hadjistavropolous, H.D. (2006). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in the Rehabilitation of a Girl With Chronic Idiopathic Pain: Are We Breaking New Ground? Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 13, 178–181.

- Hofmann, S. G., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2008). Acceptance and mindfulness-based therapy: New wave or old hat? Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1-16.

- Hofmann, S. G. (2008). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: New Wave or Morita Therapy? Clinical Psychology, Science and Practice, 5, 280-285.

The theme of these two articles is that ACT and other mindfulness-based treatments is the same as CBT, and that ACT is the same as Morita Therapy. After these articles were written Stefan Hofmann was invited and funded to speak to the ACBS community in Chicago (2007). We had a great time in respectful dialogue. Read more about this criticism in non-peer-reviewed settings and the ensuing dialogue, click on the child page"ACT is Outright Taken from Morita Therapy" below.

- Öst, L. (2008). Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(3), 296-321.

This article is in part based on proactive efforts by the ACBS community to encourage knowledgeable criticism. Lars-Goran Öst has been invited and funded to come to several ACT conferences beginning even before he was knowledgeable of ACT work, given that he was asked to play the role of an outside critic at the first World Conference in Linkoping, Sweden (2003). He was later also invited to London (2006), and Enschede, The Netherlands (2009), that last invitation coming after the article itself was available.

The theme of Lar-Goran's criticisms have been that ACT research has methodological weaknesses, and that it is not as well done as mainstream CBT research. The latter was based on a comparison of ACT studies with a matched set of traditional CBT studies. His conclusion is that ACT is not an evidence-based treatment.

Gaudiano reply: Gaudiano, B. A. (2009). Öst's (2008) methodological comparison of clinical trials of acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive behavior therapy: Matching apples with oranges? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 1066-1070.

Öst reply: Öst, L. -G. (2009). Inventing the wheel once more or learning from the history of psychotherapy research methodology: Reply to Gaudiano's comments on Öst's (2008) review. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 1071-1073.

Gaudiano rejoinder: Gaudiano, B. (2009b) Reinventing the Wheel Versus Avoiding Past Mistakes when Evaluating Psychotherapy Outcome Research: Rejoinder to Öst (2009). Brandon has replied again in a piece self-published online (in an attempt to keep the conversation flowing without the confines of the lengthy peer-review process).

The theme of the replies was that errors were made in Lar-Goran's matching and coding process, resulting in a distorted comparison, and that ACT studies are not weaker when resulting differences in population and funding are weeded out. Further, it is noted that ACT is already listed by APA as an evidence-based treatment. Lars-Goran admits that the two sets of studies are not matched in areas such as funding, and that APA lists ACT as evidence-based, but holds to his original views.

- Arch, J. J., & Craske, M. G. (2008). Acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: Different treatments, similar mechanisms? Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 5, 263-279.

A reply: Hayes, S. C. (2008). Climbing our hills: A beginning conversation on the comparison of ACT and traditional CBT. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 286-295.

The theme of the response was that ACT is part of the CBT tradition, but it is not possible to compare intellectual similarities until CBT says what it is. Efforts of the authors to do so were argued to change long standing mainstream views, which explain some of why the two could be argued to be very similar. Both the critical article and response agreed that there were good empirical issues to be explored.

Reflective of the tone of this dialogue, several ACT researchers (Georg Eifert, John Forsyth, Steve Hayes, Mike Twohig) are doing work with Michelle Craske and her colleagues trying to study the issues raised. Michelle has been invited to speak at an ACBS World Conference. She was not able to come in 2009 but we hope to hear her in the future.

- Powers, M.B., Vörding, M.B., & Emmelkamp, P. (2009). Acceptance and commitment therapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 8, 73-80.

A reply: Levin, M., & Hayes, S.C. (2009). Is Acceptance and commitment therapy superior to established treatment comparisons? Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 78, 380.

Author response: Powers, M. B., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2009). Response to ‘Is acceptance and commitment therapy superior to established treatment comparisons?’ Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 78, 380–381.

ACT researchers have critically examined the method of the meta-analysis and have published a response to the study, with a revised analysis. A counter response by Powers and colleagues is also available. We invited Paul Emmelkamp to come to Enschede but he could not ... we hope to get him to an ACBS conference in the future.

Replies to Critiques in General: Articles Describing the CBS Strategy Extensive reviews of the issued raised in this article are out or in press, but they are too extensive to simply call them "replies." The theme of the articles (which you can read by clicking the link above) has been to describe the ACT approach, its knowledge development strategy and to show its distinctive features.

Criticism: "ACT is Outright Taken from Morita Therapy"

Criticism: "ACT is Outright Taken from Morita Therapy"Getting Beyond the Way of the Guru and Other Scientific Deadends

Getting Beyond the Way of the Guru and Other Scientific DeadendsBooks

BooksThere are many books, audiobooks, and other materials to help you learn more about ACT, RFT, Contextual Behavioral Science, and related topics such as mindfulness and other third wave interventions.

There may seem like a lot of choices in some areas. And there are, which is a testament to how quickly the ACT/RFT/CBS work has grown.

ACT Books: General Purpose

ACT Books: General Purpose(The following list of books is from the LEARNING ACT RESOURCE GUIDE: The complete guide to resources for learning Acceptance & Commitment Therapy by Jason Luoma, Ph.D. Updated July 2020 learningact.com)

BOOKS FOR LEARNING ACT

- LEARNING ACT

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Theories of Psychotherapy)

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Second Edition: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: 100 Key Points and Techniques

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Contemporary Theory Research and Practice

- Acceptance and commitment Therapy: The CBT distinctive features series

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Dummies

- The ACT Approach: A Comprehensive Guide for Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- The Act in Context: The Canonical Papers of Steven C. Hayes

- ACT in Practice: Case Conceptualization in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- ACT in Steps: A Transdiagnostic Manual for Learning Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- ACT Made Simple: An Easy-To-Read Primer on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (The New Harbinger Made Simple Series)

- The ACT Matrix: A New Approach to Building Psychological Flexibility Across Settings and Populations

- The ACT Practitioner’s Guide to the Science of Compassion: Tools for Fostering Psychological Flexibility

- ACT Questions and Answers: A Practitioner’s Guide to 150 Common Sticking Points in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- The Art and Science of Valuing in Psychotherapy: Helping Clients Discover, Explore, and Commit to Valued Action Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- The Big Book of ACT Metaphors: A Practitioner’s Guide to Experiential Exercises and Metaphors in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Interventions for Radical Change: Principles and Practice of Focused Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- A CBT Practitioner’s Guide to ACT: How to Bridge the Gap Between Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Committed Action in Practice: A Clinician’s Guide to Assessing, Planning, and Supporting Change in Your Client (The Context Press Mastering ACT Series)

- A Contextual Behavioral Guide to the Self: Theory and Practice

- Contextual Schema Therapy: An Integrative Approach to Personality Disorders, Emotional Dysregulation, and Interpersonal Functioning

- The Essential Guide to the ACT Matrix: A Step-by-Step Approach to Using the ACT Matrix Model in Clinical Practice Essentials of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Evolution and Contextual Behavioral Science: An Integrated Framework for Understanding, Predicting, and Influencing Human Behavior

- Experiencing ACT from the Inside Out: A Self-Practice/Self-Reflection Workbook for Therapists (Self-Practice/Self-Reflection Guides for Psychotherapists)

- The Heart of ACT: Developing a Flexible, Process-Based, and Client-Centered Practice Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Innovations in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Clinical Advancements and Applications in ACT

- Inside This Moment: A Clinician’s Guide to Promoting Radical Change Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Introduction to ACT: Learning and Applying the Core Principles and Techniques of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Learning Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Essential Guide to the Process and Practice of Mindful Psychiatry

- Learning ACT for Group Treatment: An Acceptance and Com-mitment Therapy Skills Training Manual for Therapists

- A Liberated Mind: How to Pivot Toward What Matters

- The Little ACT Workbook

- Metaphor in Practice: A Professional’s Guide to Using the Science of Language in Psychotherapy

- Mindfulness, Acceptance, and the Psychodynamic Evolution: Bringing Values into Treatment Planning and Enhancing Psychodynamic Work with Buddhist Psychology (The Context Press Mindfulness and Acceptance Practica Series)

- Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Positive Psychology: The Seven Foundations of Well-Being (The Context Press Mindfulness and Acceptance Practica Series)

- Mindfulness- and Acceptance-Based Behavioral Therapies in Practice (Guides to Individualized Evidence-Based Treatment)

- Mindfulness and Acceptance: Expanding the Cognitive-Behavioral Tradition

- Mindfulness and Acceptance in Social Work: Evidence-Based Interventions and Emerging Applications (The Context Press Mindfulness and Acceptance Practica Series)

- The Mindfulness-Informed Educator: Building Acceptance and Psychological Flexibility in Higher Education

- A Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Talking ACT: Notes and Conversations on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Values in Therapy: A Clinician’s Guide to Helping Clients Explore Values, Increase Psychological Flexibility, and Live a More Meaningful Life

- The Wiley Handbook of Contextual Behavioral Science

- ADVANCED PRACTICE IN ACT

- ACT Questions and Answers: A Practitioner’s Guide to 150 Common Sticking Points in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- ACT Verbatim for Depression and Anxiety: Annotated Transcripts for Learning Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Advanced Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Experienced Practitioner’s Guide to Optimizing Delivery

- Advanced Training in ACT: Mastering Key In-Session Skills for Applying Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Cognitive Defusion in Practice: A Clinician’s Guide to Assessing, Observing, and Supporting Change in Your Client (The Context Press Mastering ACT Series)

- Getting Unstuck in ACT: A Clinician’s Guide to Overcoming Common Obstacles in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Inside This Moment: A Clinician’s Guide to Promoting Radical Change Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Learning ACT: An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills Training Manual for Therapists

- Learning ACT for Group Treatment: An Acceptance and Com-mitment Therapy Skills Training Manual for Therapists

- Metaphor in Practice: A Professional’s Guide to Using the Science of Language in Psychotherapy

- Mindfulness for Two: An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Approach to Mindfulness in Psychotherapy

ACT in Practice

ACT in Practice

Welcome to the companion website for the book!

Case conceptualization is an important part of any psychotherapeutic approach, and the ACT in Practice book helps therapists learn how to take clinically useful ideas from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and actually put them into practice and formulate treatments for a wide variety of clinical concerns.

The first section of the book offers an introduction to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, an overview of the impact of ACT, and a brief introduction to the ACT's "hexaflex" model. The book also describes how to accomplish case conceptualizations in general and offers review of the literature on the importance and value of case conceptualization.

The first section closes with synopsis of the first, second, and third wave of behavior therapy with explanations of how the different waves would have treated hypothetical clients in specific situations.

The second section of the book covers ways that different ACT approaches can be applied to actual practice.

Quizzes at the end of each chapter help the reader evaluate the information they have just learned.

Please click on the links below for additional information and resources!

ACT Training and Supervision by the Authors

ACT Training and Supervision by the AuthorsPatty and D.J. have been training therapists in ACT and providing supervision in clinical behavior analysis since 2001.

If you are interested in having clinical tapes and videos reviewed for “distance supervision,” or would like to organize an ACT training workshop, we would be happy to assist you.

Please contact us for further details: [email protected]

About the Authors

About the AuthorsPatricia A. Bach, Ph.D.

Patty received her doctorate from the University of Nevada in 2000. She is an assistant professor of psychology at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, where she does ACT and RFT research and trains students of clinical psychology.

Daniel J. Moran, Ph.D., BCBA

D.J. received his doctorate in clinical and school psychology from Hofstra University in 1998. He began his training in acceptance and commitment therapy in 1994 and practices clinical behavior analysis with victims of abuse and individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder. He is the founder of the MidAmerican Psychological Institute, and director of the Family Counseling Center, a division of Trinity Services, in Joliet, IL.

D.J. is also the host of Functionally Speaking – A 21st Century Behavior Therapy podcast. Listen here!

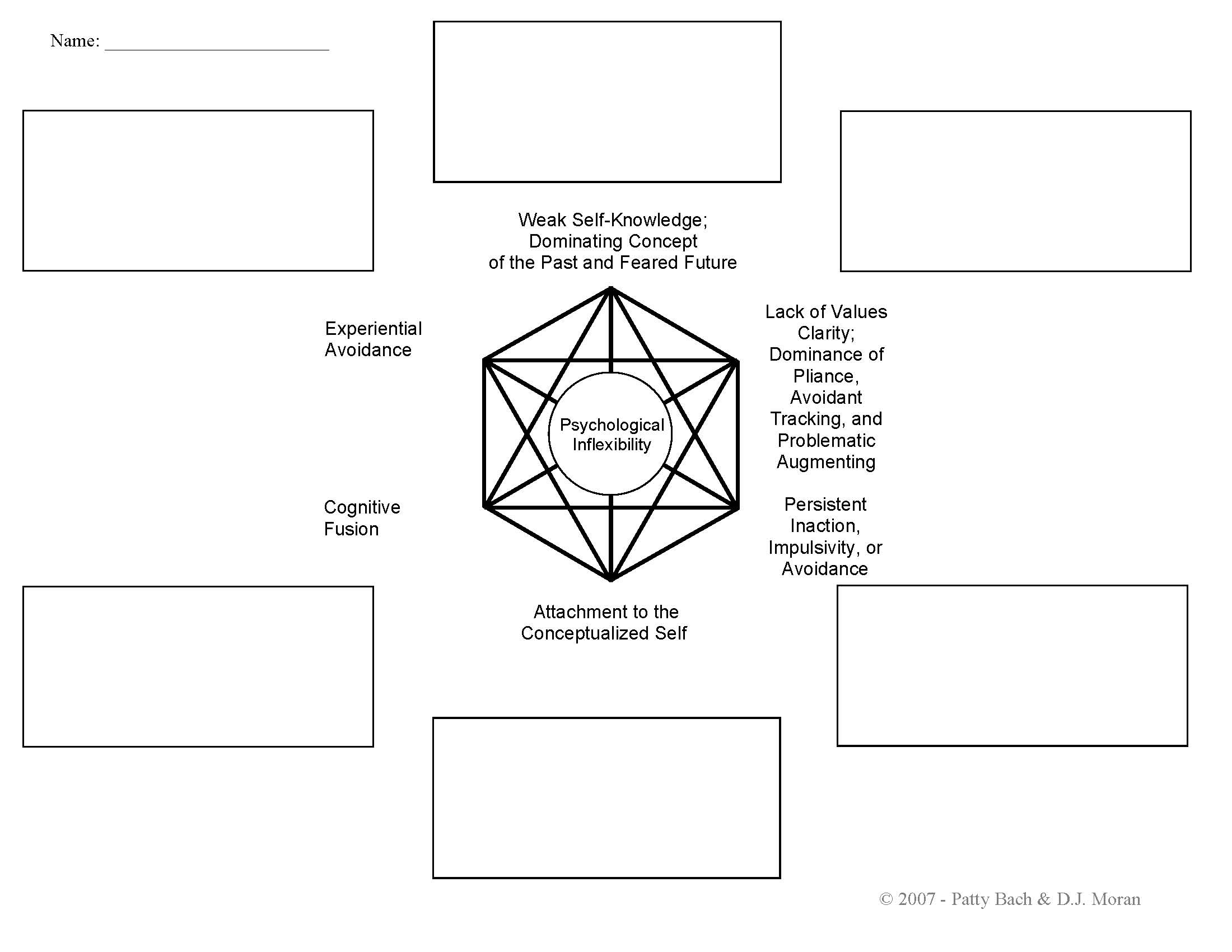

Case Conceptualization Worksheet

Case Conceptualization WorksheetThis “Inflexahex” model for case conceptualization can assist the clinician in charting and rating clinically relevant concerns in their clients’ lives. Dr. Patty Bach and Dr. D.J. Moran have made the ACT Case Conceptualization form available for download in pdf form, free to paid ACBS members. The form is also below for your convenience. You may select the image below and save it to your computer by right clicking on it and choosing "Save Image As".

If you would like a free, full-sized pdf copy of the form and are not a paid ACBS member, please email the authors for a copy at [email protected].

ACT Books: Specific Populations

ACT Books: Specific PopulationsACT Books: Specific Populations |

(The following list of books is from the LEARNING ACT RESOURCE GUIDE: The complete guide to resources for learning Acceptance & Commitment Therapy by Jason Luoma, Ph.D. Updated July 2020 learningact.com)

- ANGER

Therapist guides

- Contextual Anger Regulation Therapy: A Mindfulness and Acceptance- Based Approach (Practical Clinical Guidebooks)

Client books

- Act on Life Not on Anger: The New Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Guide to Problem Anger

- The Moral Injury Workbook: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills for Moving Beyond Shame, Anger, and Trauma to Reclaim Your Values

- ANXIETY

Therapist guides

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Ultimate Guide to Using ACT to Treat Stress, Anxiety, Depression, OCD, and More, Including Mindfulness Exercises and a Comparison with CBT and DBT

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Anxiety Disorders

- Acceptance-Based Behavioral Therapy: Treating Anxiety and Related Challenges

- ACT-Informed Exposure for Anxiety: Creating Effective, Innovative, and Values-Based Exposures Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- The Clinician’s Guide to Exposure Therapies for Anxiety Spectrum Disorders: Integrating Techniques and Applications from CBT, DBT, and ACT

- Trichotillomania: An ACT-Enhanced Behavior Therapy Approach Therapist Guide (Treatments That Work)

Client books

- The ACT on Anxiety Workbook

- The ACT Workbook for OCD: Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Exposure Skills to Live Well with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

- Anxiety Happens: 52 Ways to Find Peace of Mind

- Be Mighty: A Woman’s Guide to Liberation from Anxiety, Worry, and Stress Using Mindfulness and Acceptance

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: How to Use CBT to Overcome Anxiety, Depression and Intrusive Thoughts + A Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and ACT Techniques

- The Confidence Gap: A Guide to Overcoming Fear and Self-Doubt

- In This Moment: Five Steps to Transcending Stress Using Mindfulness and Neuroscience

- Living Beyond OCD Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: A Workbook for Adults

- The Mindfulness and Acceptance Workbook for Anxiety: A Guide to Breaking Free from Anxiety, Phobias, and Worry Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (2nd Edition)

- The Mindfulness and Acceptance Workbook for Social Anxiety and Shyness: Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to Free Yourself from Fear and Reclaim Your Life

- Outsmart Your Anxious Brain: Ten Simple Ways to Beat the Worry Trick

- Social Courage: Coping and thriving with the reality of social anxiety

- Things Might Go Terribly, Horribly Wrong: A Guide to Life Liberated from Anxiety

- Trichotillomania: An ACT-Enhanced Behavior Therapy Approach Workbook (Treatments That Work)

- The Worry Trap: How to Free Yourself from Worry & Anxiety Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- CANCER

Client books

- Flying over Thunderstorms: Living Your Life with Cancer through Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- CHILDREN/ADOLESCENTS/PARENTING

Therapist guides

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Clinician’s Guide for Supporting Parents

- Acceptance & Mindfulness Treatments for Children & Adolescents: A Practitioner’s Guide

- ACT for Adolescents: Treating Teens and Adolescents in Individual and Group Therapy

- ACT for Treating Children: The Essential Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Kids

- Challenging Perfectionism: An Integrative Approach for Supporting Young People Using ACT, CBT and DBT