Glossary

GlossaryGlossary of Terms

Cfunc

CfuncA context that controls the transformation of stimulus functions. Pronounced "cee funk." (Note: the "func" portion of this term typically appears as subscript, which is difficult to implement in HTML).

Crel

CrelA context that controls framing events relationally. While these can include nonarbitrary features of the relata in some circumstances, the same relational behavior must also be controlled by arbitrary contextual cues in other circumstances in order to define the response as arbitrarily applicable. Pronounced "cee rel." (Note: the "rel" portion of this term typically appears as subscript, which is difficult to implement in HTML).

acceptance

acceptanceAcceptance is defined in ACT as "actively contacting psychological experiences -- directly, fully, and without needless defense -- while behaving effectively." (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, & Strosahl, 1996, p. 1163)

analytic-abstractive theory

analytic-abstractive theoryOrganized sets of behavioral principles emerging from coherent sets of functional analyses that are used to help predict and influence behaviors in a given response domain.

arbitrarily applicable relational responding

arbitrarily applicable relational respondingarbitrary

arbitraryaugmenting

augmentingbehavior analysis

behavior analysisbehavioral principles

behavioral principlescombinatorial entailment

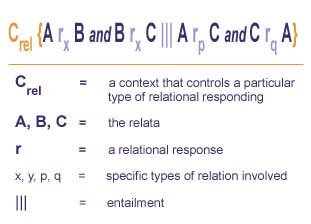

combinatorial entailmentA defining feature of relational frames that refers to the ability to combine mutually related events into a relational network under forms of contextual control that can include arbitrary contextual cues. Combinatorial entailment applies when in a given context A is related in a characteristic way to B, and A is related to C, and as a result a relation between B and C is now mutually entailed. The specific form of the network does not matter. It would be as correct to say that combinatorial entailment applies when in a given context A is related in a characteristic way to B, and B is related to C, and as a result a relation between A and C is now mutually entailed. Combinatorial entailment can be represented by the formula below.

complete relational network

complete relational networkNetworks of events containing Crel terms that set the occasion for the relational activity necessary to specify a relation between the events in the network.

contextual psychology

contextual psychologycontextualism

contextualismcontinuity assumption

continuity assumptioncoordination

coordinationdeictic frames

deictic framesDeictic relations specify a relation in terms of the perspective of the speaker such as left/right; I/you (and all of its correlates, such as "mine"; here/there; and now/then. Some relations may or may not be deictic, such as front/back or above/below, depending on the perspective applied. For example, the sentence "The back door of my house is in front of me" contains both a spatial and deictic form of "front/back." Deictic relations seem to be a particularly important family of relational frames that may be critical for perspective-taking. An example is the three frames of I and YOU, HERE and THERE, and NOW and THEN. These frames are unlike the others mentioned previously in that they do not appear to have any formal or nonarbitrary counterparts. Coordination, for instance, is based on formal identity or sameness, and "bigger than" is based on relative size. In contrast, frames that depend on perspective cannot be traced to formal dimensions in the environment at all; instead, the relationship between the individual and other events serves as the constant variable upon which these frames are based.

depth

depthdistinction

distinctionfamilies of relational frames

families of relational framesRelational frames can be roughly organized into families of specific types of relations. This list is not exhaustive, but serves to demonstrate some of the more common frames and how they may combine to establish various classes of important behavioral events.

- frames of coordination

- frames of opposition

- frames of distinction

- frames of comparison

- hierarchical frames

- deictic frames

- other families: other families of relations include spatial relations such as over/under and front/back, temporal relations such as before/after, and causal/contingency relations such as "if...then"

The foregoing families of relational frames are not final or absolute. If RFT is correct, the number of relational frames is limited only by the creativity of the social/verbal community that trains them. Thus the foregoing list is to some degree tentative. For example, TIME and CAUSALITY can be thought of as one or two types of relations. It is not yet clear if thinking of them as either separate or related may be experimentally useful, relative to the goals of RFT. Thus, while the generic concept of a relational frame is foundational to RFT, the concept of any particular relational frame is not. The purpose in constructing a list of frames is to provide a set of conceptual tools, some more firmly grounded in data than others, that may be modified and refined as subsequent empirical analyses are conducted. To see some brief examples of common families of relational frames, please watch the video families below.

formative augmenting

formative augmentingA form of rule-governed behavior controlled by relational networks that establish given consequences as reinforcers or punishers.

frames of comparison

frames of comparisonThe family of comparative relational frames is involved whenever one event is responded to in terms of a quantitative or qualitative relation along a specified dimension with another event. Many specific subtypes of comparison exist (e.g., bigger/smaller, faster/slower, better/worse). Although each subtype may require its own history, the family resemblance may allow the more rapid learning of successive members. The different members of this family of relations are defined in part by the dimensions along which the relation applies (e.g., size; attractiveness; speed). Comparative frames may be made more specific by quantification of the dimension along which a comparative relation is made. For example, the statement "A is twice as fast as B and B is twice as fast as C" allows a precise specification of the relation within all three pairs of elements in the network.

frames of coordination

frames of coordinationframes of distinction

frames of distinctionThe frame of distinction also involves responding to one event in terms of the lack of a frame of coordination with another, typically also along a particular dimension. Like a frame of opposition, this frame implies that responses to one event are unlikely to be appropriate in the case of the other, but unlike opposition, the nature of an appropriate response is typically not defined. If I am told only, for example, "this is not warm water," I do not know whether the water is ice cold or boiling hot. When frames of distinction are combined, the combinatorially entailed relation is weak. For example, without additional disambiguating information, if two events are different than a third event, I do not know the relation between these two beyond the fact of their shared distinction.

frames of opposition

frames of oppositionOpposition is another early relational frame. In natural language use, this kind of relational responding involves an abstracted dimension along which events can be ordered and distinguished in equal ways from a reference point. Along the verbally abstracted dimension of temperature, for example, cool is the opposite of warm, and cold is the opposite of hot. The specific relational frame of opposition typically (but not necessarily) implicates the relevant dimension (e.g., "pretty is the opposite of ugly" is relevant to appearance). Opposition should normally emerge after coordination because the combinatorially entailed relation in frames of opposition includes frames of coordination (e.g., if hot is the opposite of freezing and cold is the opposite of hot, then cold is the same as freezing).

framing events relationally

framing events relationallyFraming events relationally (or "framing relationally" or "relational framing") refers to a specific type of arbitrarily applicable relational responding that has the defining features in some contexts of mutual entailment, combinatorial entailment, and the transformation of stimulus functions. Framing events relationally is due to a history of relational responding relevant to the contextual cues involved; and is not solely based on direct non-relational training with regard to the particular stimuli of interest, nor solely to nonarbitrary characteristics of either the stimuli or the relation between them. The action of framing events relationally is often referred to in the noun form of "relational frame." Various families of relational frames, or ways of framing events relationally, have been identified.

functional contextualism

functional contextualismgeneralized operant

generalized operanthierarchial frames

hierarchial framesHierarchical relations or hierarchical class memberships have the same diode-like quality of frames of comparison, but the combinatorially entailed relations differ because the hierarchical relation itself is the basis for a frame of coordination. For example, if Tom is the father of Simon and Jane, then Simon and Jane are known to be siblings. If Tom is taller than both Simon and Jane, however, the relative heights of Simon and Jane are unknown. Hierarchical relations are essential to many forms of verbal abstraction.

listening with understanding

listening with understandingThe responses of listeners that are based on framing events relationally.

motivative augmenting

motivative augmentingA form of rule-governed behavior controlled by relational networks that alter the degree to which previously established consequences function as reinforcers or punishers.

mutual entailment

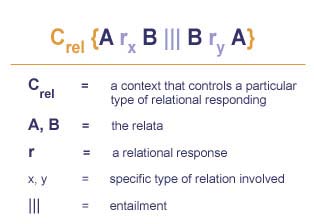

mutual entailmentA defining feature of relational frames that refers to its fundamental bidirectionality under forms of contextual control that can include arbitrary contextual cues. Mutual entailment applies when in a given context A is related in a characteristic way to B, and as a result B is now related in another characteristic way to A. Mutual entailment can be represented by the formula below.

opposition

oppositionOpposition is another early relational frame. In natural language use, this kind of relational responding involves an abstracted dimension along which events can be ordered and distinguished in equal ways from a reference point. Along the verbally abstracted dimension of temperature, for example, cool is the opposite of warm, and cold is the opposite of hot. The specific relational frame of opposition typically (but not necessarily) implicates the relevant dimension (e.g., "pretty is the opposite of ugly" is relevant to appearance). Opposition should normally emerge after coordination because the combinatorially entailed relation in frames of opposition includes frames of coordination (e.g., if hot is the opposite of freezing and cold is the opposite of hot, then cold is the same as freezing).

pliance

plianceA form of rule-governed behavior under the control of a history of socially-mediated reinforcement for coordination between behavior and antecedent verbal stimuli (i.e., the relational network or rule), in which that reinforcement is itself delivered based on a frame of coordination between the rule and behavior. Stated another way, pliance requires both following a rule and detection by the verbal community that the rule and the behavior correspond. Mere social consequation does not define pliance. The rule itself is called a ply.

pragmatic verbal analysis

pragmatic verbal analysisFraming events relationally under the control of abstracted features of the nonarbitrary environment that are themselves framed relationally. Stated in other words, pragmatic verbal analysis involves acting upon the world verbally, and having the world serve verbal functions as a result.

See below for an illustration of RFT's interpretation of pragmatic verbal analysis/problem solving.

precision

precisionproblem solving

problem solvingAlthough problem-solving has both non-verbal and verbal connotations, in a verbal sense problem-solving refers to framing events relationally under the antecedent and consequential control of an apparent absence of effective actions. When the particular problem involves the stimulus functions of the nonarbitrary environment, verbal problem-solving can be said to be pragmatic verbal analysis that changes the behavioral functions of the environment under the antecedent and consequential control of an apparent absence of effective action.

See below for an illustration of RFT's interpretation of pragmatic verbal analysis/problem solving.

relata

relatarelational frame

relational frameA specific type of arbitrarily applicable relational responding that has the defining features in some contexts of mutual entailment, combinatorial entailment, and the transformation of stimulus functions. Relational frames are due to a history of relational responding relevant to the contextual cues involved; and is not solely based on direct non-relational training with regard to the particular stimuli of interest, nor solely to nonarbitrary characteristics of either the stimuli or the relation between them. While used as a noun, it is in fact always an action and thus can be restated anytime in the form "framing events relationally." Various families of relational frames have been identified.

relational network

relational networkA relational frame is the smallest relational network that can be defined, although the term network is usually used to refer to combinations of relational frames, such as A is more than B, B is the same as C, C is less than D. The term network is also used to describe relations between or among relational frames, such as, if A is more than B, and C is more than D, then the relation between A and B participates in a frame of coordination with the relation between C and D.

relational responding

relational respondingResponding to one event in terms of another. See below for an illustration depicting the difference between relational responding and non-relational responding.

rule-governed behavior

rule-governed behaviora.k.a., RGB

In its most general terms, behavior controlled by a verbal antecedent. However, behavior controlled by verbal antecedents is more likely to be termed "rule governed" if the verbal antecedent forms a complete relational network that transforms the functions of the nonarbitrary environment.

See below for an illustration of RFT's interpretation of rule-governed behavior.

scope

scopeScope means that a broad range of phenomena can be analyzed with a given set of analytic concepts (the broader the range the better, so long as precision is not compromised).

strategic problems

strategic problemsThose verbal problems in which the problem solver has placed the desired goal or purpose into a relational frame.

thinking

thinkingtracking

trackingA form of rule-governed behavior under the control of a history of coordination between the rule and the way the environment is arranged independently of the delivery of the rule. The rule itself is called a track.

transfer of stimulus functions

transfer of stimulus functionsA specific type of transformation of stimulus functions between two relata when they participate in a frame of coordination.

transformation of stimulus functions

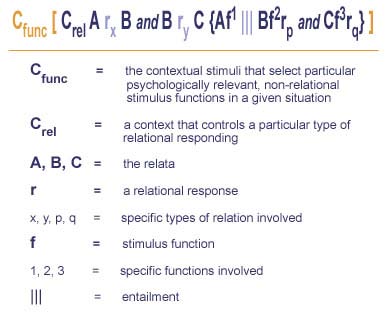

transformation of stimulus functionsA defining feature of relational frames that refers to the modification of the stimulus functions of relata based on contextual cues that specify a relevant function (Cfunc) and the relational frame that these events participate in (Crel). The transformation of stimulus functions can be represented by the formula below.

valuative problems

valuative problemsThose verbal problems in which the goal is to place a desired goal or purpose into a relational frame.

varieties of relational frames

varieties of relational framesRelational frames can be roughly organized into families of specific types of relations. This list is not exhaustive, but serves to demonstrate some of the more common frames and how they may combine to establish various classes of important behavioral events.

- frames of coordination

- frames of opposition

- frames of distinction

- frames of comparison

- hierarchical frames

- deictic frames

- other families: other families of relations include spatial relations such as over/under and front/back, temporal relations such as before/after, and causal/contingency relations such as "if...then"

The foregoing families of relational frames are not final or absolute. If RFT is correct, the number of relational frames is limited only by the creativity of the social/verbal community that trains them. Thus the foregoing list is to some degree tentative. For example, TIME and CAUSALITY can be thought of as one or two types of relations. It is not yet clear if thinking of them as either separate or related may be experimentally useful, relative to the goals of RFT. Thus, while the generic concept of a relational frame is foundational to RFT, the concept of any particular relational frame is not. The purpose in constructing a list of frames is to provide a set of conceptual tools, some more firmly grounded in data than others, that may be modified and refined as subsequent empirical analyses are conducted. To see some brief examples of common families of relational frames, click on the video below.

verbal behavior

verbal behaviorThe action of framing events relationally.

verbal stimuli

verbal stimuliStimuli that have their effects because they participate in relational frames.